As a child I got hooked by Sherlock Holmes quite young. I can’t recall exactly when I first starting reading the Conan Doyle stories, but definitely had read them all by the time I hit junior high. I was drawn by the scientific method of the man and the riddles of the mysteries. Over the years I have also seen various Sherlock movies. I never saw the Basil Rathbone b&w classics. Instead, my two favourites are both from the 70s/early 80s, and are very different in their approaches.

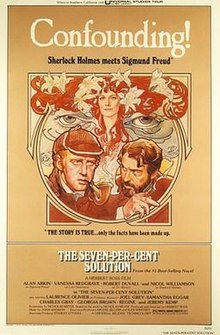

The first is The Seven Percent Solution, which brings Holmes (Nicol Williamson) together with Sigmund Freud (Alan Arkin—one of my favourite comedic actors in a rare dramatic role), who tries to rid Holmes of his heroin addiction through hypnosis.

The second is Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter Brother, starring Gene Wilder as Sigerson Holmes, Sherlock’s maniacally jealous and determined younger brother. It is the best Mel Brooks movie that Mel Brooks never wrote (it was written by Wilder) and has a stupefyingly funny supporting cast (Marty Feldman; Madeleine Kahn; Leo McKern). The movie was out of print for so long, coming to DVD only recently with a devastatingly deadpan commentary from Wilder himself who critiques his own performance mercilessly. I cannot recommend it enough.

About the newest Sherlock Holmes movie (with Downey Jr and Law) I will say little, only that it shares the title and general setting of the original story and little else. Much as I enjoyed the performances of the two main characters, the rest of it was (in my opinion) a total defilement of the Holmesian mystique.

But back to the game...

I did not play 221B Baker Street when it came out, although I definitely remember it from later childhood or early adolescence—possibly from a writeup in Games Magazine. The copy I played this week is one I obtained in a Math Trade in my local gaming group.

I played at Snakes and Lattes, a cafe which opened up at the end of the summer of 2010 about a 10-minute walk from my work. They boast a library of over 1500 boardgames, which is available for a cover charge of $5. Some of us in our gaming group weren’t sure if this combo of games, food, and drink was going to succeed; cafes and restaurants make money from high turnover, and boardgames take time (and don’t take kindly to crumbs or spilled liquids). Not to mention that gamers are a pretty skinflinty lot; they usually resent having to “pay to play” anywhere, and will bring their own food and drink rather than pay for it.

It turns out, however, that the crowds who frequent S&L (and most nights there are crowds) are not gamers, but instead younger, hipper people most of whom are either (a) nostalgic for games from their childhood like Sorry; or (b) looking to play party games like Taboo. A few are genuinely curious about the ‘other’ games with strange names and funny wooden pieces—or become so after watching others.

S&L has also obtained a liquor license, which means it is even more attractive to those looking to go out and relax somewhere without the intensity of a bar or dance club.

The real strength of the cafe, however, is the staff, who are generally quite knowledgeable about games, willing to teach, and aren’t shy about bringing together patrons to play games—which is in fact what happened to me this week. I was sitting alone at a table having dessert and waiting to see if any of my TABS friends would turn up, when one of the ‘game-ista’s shook me out of my reverie and asked me if I was up for a game of something with a guy sitting at the table behind me who was similarly by himself.

I ended up spending a very enjoyable evening with the guy, by the name of Rob, playing through various games (starting with 221B Baker Street and then moving on to 7 Wonders, Haggis, Erosion, and What’s My Word). None of that would have happened except for the intervention of the guy behind the counter.

THE GAME

221B Baker Street is the first “oldie” on my list; according to BoardGameGeek, it was originally released in 1975. It has worn quite badly with the years. To begin with, the board is a purported ‘map’ of London upon which players move their generic plastic pieces from place to place by rolling a die. The game comes with twenty “cases”. As players move around the board they can enter buildings which give them clues to solve the mysteries. The first player who returns to 221B Baker Street (Holmes’ HQ) and correctly solves the mystery wins the game.

That is the gist of the game. There are a couple of other rules which allow players to ‘seal off’ locations (and naturally to ‘unseal’ them), but they are a crucial part of the game. In its day I think it broke some ground, and parents who are looking for something to play with 6 – 9 year-olds could probably enjoy it on Family Game Night. Hard-core gamers would probably not enjoy it (for alternate suggestions, read on).

|

| Queen Nefetari playing Senet, 13th century BCE |

And of course, there’s Monopoly.

Backgammon introduced some real innovation by using two dice and allowing players to decide whether to split the roll into two separate moves. (Many would argue the doubling cube also adds a whole layer to the game—but only if you play for stakes.)

There are newer games (That’s Life comes to mind) which take roll-and-move and add real strategic decision-making without losing the fun (and heartbreak) (and frustration) of relying on little cubes to tell you how far to move your pieces.

The fact that in 1975 it was still perfectly ok to make a game for adults using a roll-and-move mechanic tells you a lot about the state of the hobby at the time.

The cases are well-written, but the useful clues are randomly spread around the board; it would have been better to place the best clues in locations related to the case. Furthermore, some of the clues are wordplay-oriented (ie, “Killer Clue First Part: not short.” “Killer Clue Second Part: pal.” The solution: long + fellow = Longfellow). I can imagine the designers realizing they had a lot more locations on the map than they had good clues and decided to pad them out. The result really doesn’t fit the Holmes theme.

CONCLUSION

Rob and I rolled the die and moved around the board. Within about ten minutes I’d entered enough locations and was lucky enough to have found enough good clues to solve the mystery. With good die rolls I made it back to 221B and solved the case. Big Deal; I didn’t even care that I had it right.

As I said above, as a kiddie game it’s fine, but for grown-ups Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective is far better. As for other mystery games, I can recommend any of the Mystery Rummy series, and Mystery Express is a new take on the genre. There is also a related genre of game where the mystery lies in figuring out which player (or players) are the traitors trying to subvert victory (Shadows Over Camelot, Battlestar Galactica, The Resistance).

For strict deduction games, Code 777 is an intense exercise and Tobago is a treasure-hunting game with gorgeous components and some fine deductive mechanics. Finally, What’s My Word is a Mastermind-with-words game from the same era as 221B Baker Street but which holds up just as well today as it did then.

NEXT WEEK: 7 WONDERS—flavour of the month or classic in the making?

No comments:

Post a Comment